Renato Redentor Constantino, Constantino Foundation

What remains of Carlos Fressel? There are several answers to the question. Among them is a reminder to Filipinos about the value of our fascinating past and why history should not be treated as the domain of historians alone.

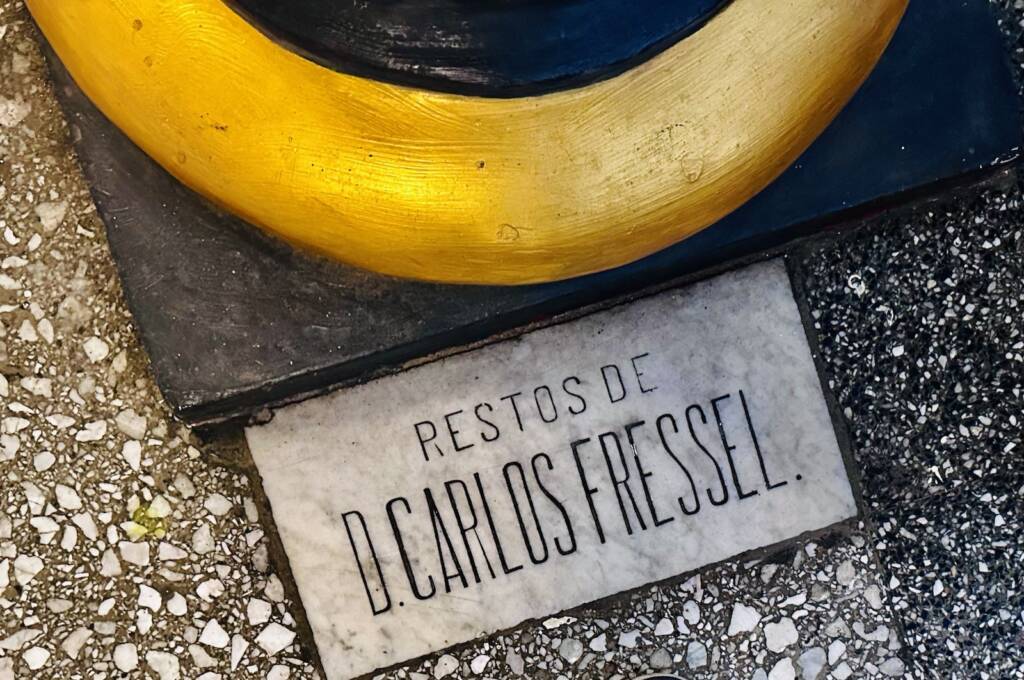

At the base of an elegant pillar in the parish of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in Sta. Mesa Manila, a curious churchgoer will find an interesting marking: Restos de D. Carlos Fressel. It means “Remains of D. Carlos Fressel.

Who exactly is D. Carlos Fressel and what explains his presence inside a church over a century old? Was he Carl Fressel, owner of the company where the great Andres Bonifacio worked, before leading the Revolution that would throw off the yoke of Spanish colonialism? Or was he one of his nine children with his wife, Elvira?

Elvira’s husband was Carl Victor Fressel, born 13 February 1856 in Luneburg, then part of the Kingdom of Hannover in today’s Germany. Carl died at the age of 48, on 4 September 1904. Yet the Sacred Heart of Jesus Parish was erected by Catalonian Capuchins in Santa Mesa only in 1911. Thankfully, the history of the parish provides a lovely clue.

Santa Mesa was a mere barrio of Sampaloc speckled with the homes of destitute families emigrating from the provinces in the first years of the 20th century. Parish history recalls a Jesuit priest was able to “celebrate mass and administer some baptisms” thanks to the effort in 1903 of “a certain Mrs. Fressel [who] built a small chapel on the same site on which stands the present church.” It is likely this is the same woman Carl married, Elvira Motell Fressel, born in Barcelona on 20 March 1867 and who died 7 December 1933 in Melle, Belgium.

Thanks to PUP historian Narciso L. Cabanilla, who pointed the author to Fressel’s memorial, a storied parish that once housed a humble chapel has revealed a compelling piece in the historical puzzle that is the Philippines.

Great efforts have been exerted in distilling the country’s revolutionary past, centered on the Katipunan and the great Andres Bonifacio. The revolution that broke out in 1896 was more than just a war for independence against Spain. It was, foremost, a revolution for dignity and ginhawa, a word that even for Filipinos today steps beyond the pedestrian translation of ‘well-being’ and ‘the good life’. Ginhawa also means ease of breathing, for those with pulmonary illnesses, but it can also mean freedom from need, “heaven on earth”, a lightness of body, a healthy physical state free from injuries, a pure heart, and most importantly, it conveys a measure of contentment. Are these not the very conditions that PUP as an educational institution aims to produce?

A bit of well-being must have been the case for Bonifacio who worked in the 1880s at the British-owned company, J.M. Fleming, headquartered in Binondo. Five years later, Bonifacio would move to the German trading firm C. Fressel Co., presumably, as the historian Jim Richardson noted, “in order to earn a higher wage.”

But why are Fressel’s remains in Sta Mesa when the company’s office address is Calle Nueva in Binondo? Nick Joaquin wrote in 1977 that Bonifacio had worked “as a bodeguero for a mosaic tile factory in Santa Mesa, which was owned by the Preysler family.” Joaquin took note of the observations of the Spanish patrona, Doña Elvira Preysler, who “is said to have recalled … that the young Bonifacio was a voracious reader.” Indeed, Preysler “noticed that [Bonifacio] had a book propped open in front of him even while he was eating lunch.” Richardson adds that the same factory seems to have been acquired “by Fressel, and came to be known during the American era as the Santa Mesa Cement, Tile, and Pipe Factory.”

Indeed, as Vol. VIII of the Philippine Commission under the U.S. War Department noted in its annual report in 1908, “The first factory to be established in the Orient for the manufacture of cement tile and pipe was the one that to-day bears the name of the Santa Mesa Cement Tile and Pipe Factory, situated on the bank of the Pasig River at Santa Mesa, Manila. This institution was founded by Mr. Carl Fressel in 1886 and he continued as proprietor until his death in 1904. When first opened it was situated on the Santa Mesa road but was later transferred to its present site in order to have the benefit of water transportation.”

Based himself in Sta. Mesa, Cabanilla’s sleuthing provides exciting leads. His find begs the question: where exactly along the Pasig was Fressel’s factory located? PUP professor Diosdado Franco, whose keen historical eye is focused on reconstructing the history of the Sta. Mesa Hipodromo—which preceded the San Lazaro race track—suspects Fressel’s industrial plant to be “somewhere along the right banks to the west of the Pasig River, not very far from where PUP is located,” while the Hipodromo de Santa Mesa was most probably within the Mabini campus of the university. It’s a compelling notion and as Franco suggests, more research is needed.

The factory must have produced colored cement products similar to the Machuka and Kalayaan tiles still made by hand today. A philatelist Nigel Gooding, long compiling Spanish-Philippine postal exchanges, including transactions, business handstamps, and postcards by and from Fressel, noted, “One advantage of the [Fressel] cement brick that appeals to the householder is the tenacity with which it retains its color, and this does away with the necessity of painting a house in the construction of which this brick is used exclusively. The brick is carefully polished, so it may be easily washed and still retain its brightness

The company continued to operate even after Fressel passed away, trading as late as 1917 when its manager, George Ludewig, previously Fressel’s assistant, was detained in Russia with the outbreak of World War I: C. Fressel & Co., a German business, was seized under the ‘Trading with the Enemy Act’ of the US, which called for the sequestration of enemy property during the period of hostilities.

As for Bonifacio, before the revolutionary upheaval, his stint in Fressel’s company helped sustain his intellectually ravenous mind. Richardson shared the observation of Katipunera and Bonifacio sister Espiridiona who said her older brother initially earned P12 a month but “over the years his wages rose substantially, up to P20 a month according to his friend Guillermo Masangkay and up to P25 according to another source. Contemporary sources describe his position simply as a bodeguero (warehouseman), but his salary, at least double that of a laborer at the time, suggests that his duties included office or sales work as well as manual work. Whatever his exact responsibilities, employment in the capital’s foreign owned businesses offered good opportunities for advancement.” A British observer, wrote Richardson, noted the way men of position began their ascent as “messengers, warehouse-keepers, clerks… of … foreign houses.”

Fressel’s company was beneficial to the Katipunan in many ways. The revolutionary movement had adopted a triangle method for recruiting members to maintain secrecy. After the formation of the first group of three, to form a new triangle each revolutionist would recruit two more who, in theory, would not know the recruits in other triangles. Bonifacio’s triangle was “with his baptismal sponsor Vicente Molina (a concierge at the government treasury) and his future wedding sponsor Restituto Javier (one of his fellow employees at Fressel’s trading company).”

Bonifacio was always a voracious reader, consuming law and medical books and, among other books, material by the French writer Alexander Dumas, Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables, Lives of the Presidents of the United States, the History of the French Revolution, and Rizal’s Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo.

Sylvia Ventura, author of Supremo: The Story of Andres Bonifacio, once wrote how Bonifacio, “Shutting a book … would announce to Nonay (Espiridiona) that he had just completed a course in law or in medicine.”

Gooding reminds us “It is worthy to note that Andres Bonifacio worked for an unconfirmed duration at Fressel and Company up to 1896. He started as a bodegero (warehouse worker) and supply clerk, later being promoted to Sales Agent in 1892. It has been stated that the warehouse served as his library and study room.”

By 23 June 1896, four years after the Katipunan was established, the Supremo is identified for the first time as a person of interest in a Spanish intelligence report: “Also to be watched is an individual named Andres Bonifacio, who is an employee of Fressel y Cia, where he is known for good conduct, who is a Mason and is making a lot of subversive propaganda (propaganda filibustera) in the districts of Tondo, Trozo and Santa Cruz.

Primary sources:

Annual Reports of the War Department Vol. 8: Report of the Philippine Commission. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1908.

Secondary sources:

“Andres Bonifacio: Myths, Trivia, Execution,” Jee Y. Geronimo, Rappler.com, 30 November 2013. https://www.rappler.com/nation/andres-bonifacio-myths-trivia-execution/

Website of the Sacred Heart of Jesus Parish, Sta. Mesa, Manila. https://www.rcam.org/sacredheartofjesusparish/

University of the Philippines Diksiyonaryong Filipino https://diksiyonaryo.ph/search/ginhawa

Gooding, Nigel. Philippine Business Firms, C Fressel & Company

Joaquin, Nick. A Question of Heroes (Makati: Ayala Museum, 1977)

Instagram account of Kalayaan Tiles https://www.instagram.com/kalayaantiles/

Machuka Tiles website https://machucatile.com/

Richardson, Jim. Andres Bonifacio, Biographical Notes Part I: January 1863- 1891

Richardson, Jim. Andres Bonifacio, Biographical Notes Part II: 1892-1895

Richardson, Jim. Andres Bonifacio, Biographical Notes Part III: January 1896-August 19, 1896

Sintang Lakbay is a historical walk and bike ride to promote inclusive mobility by facilitating active interaction with urban landscapes, restoring working-class memory in national history, and mobilizing public contributions to remembering through art and research. It is a collaborative project by The Polytechnic University of the Philippines, 350 Pilipinas, and the Constantino Foundation