Rio Constantino

“In all the terrible solitude of the winter sea, Ged stood and saw the thing he feared…At that Ged lifted the staff up high, and the radiance of it brightened intolerably, burning with so white and great a light that it compelled and harrowed even that ancient darkness. In that light all form of man sloughed off the thing that came towards Ged. It drew together and shrank and blackened, crawling on four short taloned legs upon the sand.”

As a child I grew up with fantasy and science-fiction novels. The worlds of Dune and The Wheel of Time were my playgrounds. I remember one day being driven out of the house to play with the other kids. In response I snuck out with me a novel of Drizzt, the scimitar wielding elf, and sat down on a pile of gravel (there was construction going on in the street) for my daily dose of sword-and-sorcery.

In retrospect, most paperbacks about orcs and elves and wizard’s towers suffer from stale writing. Too many adjectives, stilted cadence and rhythm, at times atrocious dialogue. How, then, could I have ever liked the stuff? The answer lies in the fighting.

I would inevitably skim past a good 2/3 of the plot to zoom in on the action: big battles, bloodstrewn battlegrounds, asteroid fields littered with charred debris. There was no skirmish worth skipping on, no duel that could be ignored. Boom! Zap! Kapow! And, because the plots were often framed in terms of good vs. evil, with a guy holding the Sword of Justice or something leading the charge, I absorbed a faulty lesson: bravery consists of mowing down hordes of faceless enemies, and at the peak of action, sticking the pointy end into the face of overwhelming evil. For years I subscribed to a hack ’n’ slash vision of courage.

And then I met Ms. Ursula K. Le Guin.

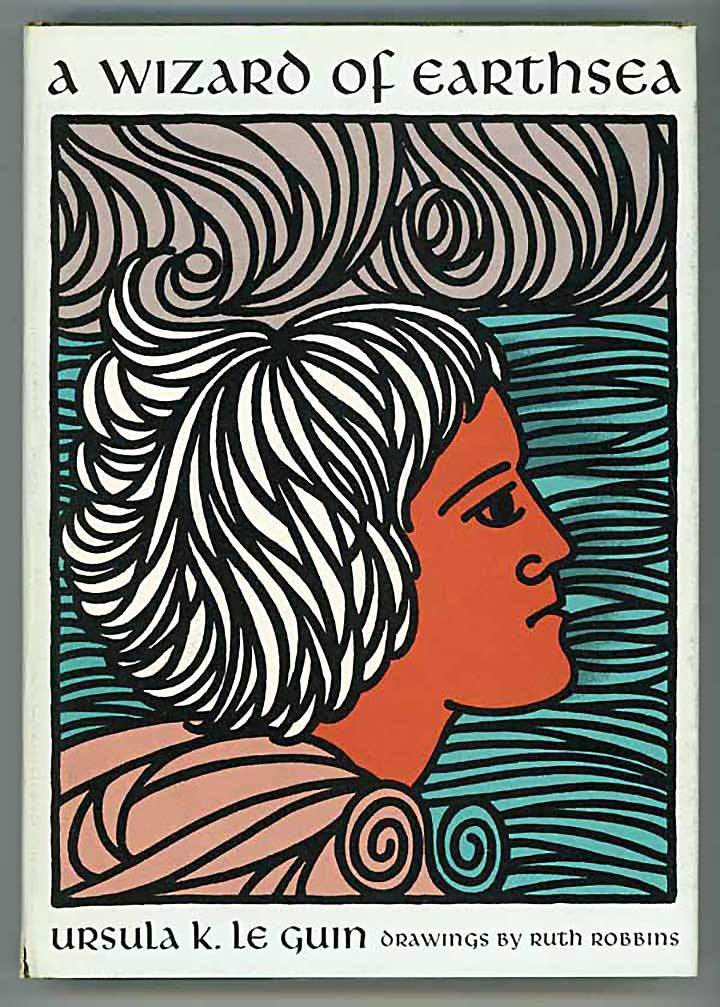

Robbins, R. (1968). Cover for “A Wizard of Earthsea”.

I first read “A Wizard of Earthsea” in my early teens. The story is about the wizard Ged in his youth, before he became a famous hero of Earthsea. As a child born in the stormy island of Gont, Ged shows considerable magical talent; inevitably, he makes mistakes. Arrogant, impatient, and awash in power, he refuses his old master Ogion’s wisdom and patience. He is sent away to train in Roke, the isle of wizards, where he inadvertently summons his doom.

Goaded into a contest of strength by a rival student, Ged utters an unspeakable spell. Three times he calls the name of a spirit from the land of the dead, and from the torn veil emerges a shadowy thing, alien and black, that leaps onto Ged’s face with claws outstretched. At the last minute, he is saved by the old archmage, Nemmerle. But the damage is done: Nemmerle dies, and Ged’s face is hopelessly disfigured. Worse, the shadow escapes. When Ged, scarred and remorseful, eventually finishes his training and leaves the safety of Roke’s walls, he is horrified to discover his shadow has been lying in wait. Ged flees and is chased.

The world of Earthsea was both like and unlike every other fantasy land I had encountered until then. Most of the people scattered across the archipelago – because there are no continents in Earthsea, only numerous small islands – are brown-skinned or black. The last king in Havnor died ages ago; most polities are fractious island holdings, and conflict usually comes in the form of pirates and raids. The essence of magic lies in keeping the balance. Time passes slowly. Some of the most spellbinding parts of the story occur when nothing much is happening at all: moonlight falling on a grove, Ged adrift on grey seas, a bonfire.

Even stranger, there is no clear antagonist. True, there was a big dragon at one point, and an ancient spirit sealed in a stone, but they were just passing encounters, not overarching villains. The main arc, really, was just Ged fleeing his shadow. In other words, fleeing himself.

What really threw me off was how violence refused to work on Ged’s enemy. In his fear, no matter how much Ged tried to strike a blow with his staff, or channel a bolt of lightning, the shadow would always flutter back up again. The escape continued. As a wizard said to Ged about the evil he summoned, “The power you had to call it gives it power over you: you are connected. It is the shadow of your arrogance, the shadow of your ignorance, the shadow you cast. Has a shadow a name?”

Sticks and stones were useless. How could courage take root then?

In the end Ged, chased all the way back to his island home of Gont, and tired of hiding, takes a staff shaped for him by his master Ogion before setting sail east for the open sea. There, seeing the evil approach, he sets his staff alight to meet it. He summons a wind into his sail, faces his shadow and –

“In utter silence, the shadow, wavering, turned and fled.”

Ged gives chase.

Stories have power. During uncertain times a good story can serve as a guiding light, and in the turmoil of recent days I find myself remembering Ged’s. I imagine Le Guin would be pleased. In one of her essays she writes: “For fantasy is true, of course. It isn’t factual, but it is true.”

In the farthest reaches of the open sea, where no man or woman has sailed beyond, water turns to sand, and the stars above are like no other, set in a sky that sees no dawn. Ged’s boat stops on a strange and sudden shore. He climbs off. The object of his chase waits in the distance. Man and shadow walk towards each other, until their faces almost touch.

“Aloud and clearly, breaking that old silence, Ged spoke the shadow’s name, and in the same moment the shadow spoke without lips or tongue, saying the same word: ‘Ged’. And the two voices were one voice.”

Light and darkness joined at last; Ged is whole again.