By: Chuck Baclagon

Five years ago, I stood in front of the control room of the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant (BNPP), listening to an engineer trying to convince us that it was safe and wise to operate the 32-year-old facility.

At the time, I thought that the debate about the safety of reviving the BNPP was finally laid to rest, given that beyond the geological arguments against operating it safely, the technology it utilizes is already put to shame by the biometric security systems that are already common in regular office spaces.

To my surprise, last June I saw this interesting sponsored post in Facebook from a page called Clean Energy Philippines espousing nuclear energy as a clean alternative to fossil fuels. I was alarmed as my experience as a digital campaigner tells me that perhaps something sinister is looming in the horizon.

Analog knobs and switches from the mainframe computer surround the control room of the mothballed Bataan Nuclear Power Plant, in the Philippines. Photo: Albert Lozada

Unfortunately this fear was not unfounded; the proposal to revive the BNPP was announced last week during an international nuclear power conference. Philippine energy secretary Alfonso Cusi told journalists on the sidelines that the country should consider nuclear power to address power shortages and the high cost of electricity. He added that the government is already working on a road map and consulting experts on nuclear power to ensure the long-term supply of “clean and cheap” electricity for the country.

The statement was generally welcomed by people online, with only statements from the Philippine Movement for Climate Justice, the Nuclear-Free Bataan Movement and Greenpeace Philippines coming out as dissenting voices to the apparent welcome chorus for a late-coming nuclear revival in the Philippines.

Nuclear power is not a cleaner and cheaper alternative to fossil-fuels, and it is not a viable energy solution for reducing greenhouse gasses. Here are the reasons why:

Economics: do the numbers add up in favor of nuclear power?

Me taking a tour of the BNPP’s main control center, taken in 2011, when Greenpeace initiated the exploratory tour in support of an announcement made by the Department of Tourism that it intends to make the plant useful by transforming it into a tourist attraction. Photo: Beau Baconguis

Nuclear power requires investments in construction; operations and maintenance, including for uranium fuel; waste storage; and decommissioning. A detailed examination of these costs reveal that at all stages of a nuclear power plant’s lifetime and beyond, from its proposal to waste storage, nuclear power is a losing proposition for the Filipino people.

The experience of countries with previous or existing nuclear programs show that nuclear power construction has gone consistently over-budget, two to three times higher than what the nuclear industry estimates.

Rehabilitation and construction costs have also twice to even thrice exceeded the estimated budget. For operational costs, procurement of uranium fuel is not cost-effective and is volatile to larger price hikes. In 2016, the European Commission assessed that European Union’s nuclear decommissioning liabilities were seriously underfunded by about 118 billion euros, with only 150 billion euros of earmarked assets to cover 268 billion euros of expected decommissioning costs covering both dismantling of nuclear plants and storage of radioactive parts and waste.

We will also be subjecting the Filipino people to greater dependence on foreign fuel, especially because the Philippines has no natural resource for uranium and only three countries are in control of 58% of its production worldwide.

Plants are not decommissioned until years after they have been shut down, and the costs will not be incurred until then. Waste storage is another problem. Even if we allocate a specific sum for the storage of nuclear wastes, the long-term radioactivity of nuclear wastes can outlive and outlast any facility constructed and will defy any sort of economic planning.

The greatest cost of a nuclear facility is the possibility of a nuclear accident. A nuclear fall out results in the depletion of nutrients found in arable land and health defects to people exposed to radiation and their descendants. The cost of such an accident to lives and livelihood is immeasurable. The cost to public finance includes evacuation plans, relocation of communities, plant repairs, and rehabilitation of surroundings.

Safety: Can we really use nukes safely in the Philippines?

The BNPP site has an unacceptably high risk of serious damage from earthquakes, volcanic activity, or both. Geological studies and findings conclude that the plant’s vicinity is filled with tectonic and volcanic activity that poses a great threat to the public’s safety.

Screen capture of a paid Facebook promotion from Clean Energy Philippines.

The plant is in the vicinity of Manila Trench–Luzon Trough tectonic structures, and risks being at the epicenter of high magnitude earthquakes. The plant also sits on Mt. Natib, a caldera-forming volcano with very powerful eruptions separated by long repose periods. If Natib erupts, pyroclastic flows could overwhelm Napot Point. Subic Bay, located west of Mt. Natib, has faults that are active roughly every 2,000 years, and the last activity was 3,000 years ago. The Lubao Lineament, suspected to be a fault, may also extend under Mt. Natib.

Should the BNPP be rehabilitated, it will violate the Provisional Safety Standards Series no. 1 of the International Atomic Agency (IAEA). Reviving the BNPP without a resolution to these scientific concerns will put the larger public in grave danger of nuclear and geological catastrophes.

Time and time again, the industry has demonstrated that nuclear safety is a contradiction in terms.

Safe reactors are a myth. An accident can occur in any nuclear reactor, causing the release of large quantities of deadly radiation into the environment. Radioactive materials are regularly discharged into the air and water even during normal operations. The policy of secrecy, which surrounded the development of the bomb, was transferred to civil nuclear power projects after World War II and lives on today.

The Guardian has a comprehensive list of nuclear related disasters that should serve as a clear warning to err in the side of caution in plans to revive the BNPP.

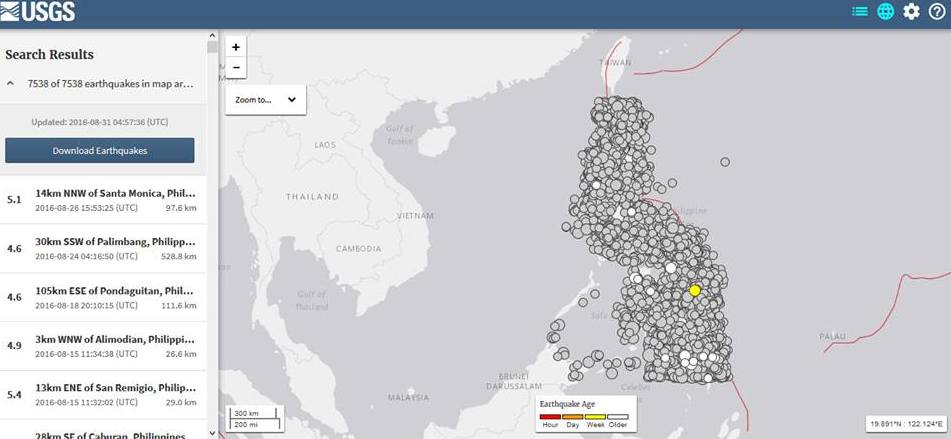

Data visualisation of earthquake data from Year 2000-2016 taken from the United States Geological Survey shows that there have been 7,538 earthquakes of varying magnitudes in the Philippines. Visualization by Leonard Soriano

Climate solution: Is nuclear the silver bullet for decarbonization?

The Facebook page of Clean Energy Philippines claims that the Philippine government should recognize nuclear power, particularly in the aftermath of the Paris climate talks, because of its near-zero carbon dioxide lifecycle and the widespread availability of uranium as fuel.

At face value, nuclear power looks like a proactive solution to climate change and energy security. But its disadvantages clearly and heavily outweigh whatever perceived benefits it can offer. Studies show that the entire nuclear power plant life cycle contributes significantly to climate change. Nuclear power will also not reduce our dependence on foreign fuel: Aside from the fact that over half of the global uranium supply comes from only three countries, it can only be processed and enriched by six countries, and then reprocessed in just one country.

The claim that nuclear power plants will lessen emission of harmful gases into the atmosphere and will not worsen climate change is false. Uranium mining, milling, plant construction, and decommissioning all produce substantial amounts greenhouse gases.

The IAEA itself estimates that wind and solar energy generators are 50 and seven times less carbon-intensive than nuclear plants, respectively.Every kilowatt-hour (kWh) of renewable power avoids the emission of more than one pound of carbon dioxide.

Thousands during a prayer rally against the re-opening the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant, in front of St. Joseph Cathedral in Balanga, Bataan. Photo: AC Dimatatac/Greenpeace

Recently, a member of the European Chamber of Commerce of the Philippines said there is no reason for the Philippines to consider nuclear power in its energy mix given the range of alternative options that the country has, not to mention the high risks and costs associated with harnessing it as seen in other first world countries.

There is no question that nuclear energy distracts governments from taking the real global action necessary to tackle climate change and meet the people’s energy needs.

Baseload: Can we really power a nuclear-free world?

Before we talk about the need for power we must also first realize that we are currently doing a terrible job at energy efficiency. For example, night time energy demand is much lower than during the day, and yet we waste a great deal of energy from coal and nuclear power plants, which are difficult to power up quickly, and are thus left running at high capacity even when demand is low. Baseload demand can be further reduced by increasing the energy efficiency of homes and other buildings.

In spite of this,the nuclear industry argues that renewable energy can’t meet baseload demand. However, the current shift of countries like Sweden and Germany to go renewable, and the story of Costa Rica being able to power 285 days of 2015 on renewable energy, demonstrate that a transition to 100% energy production from renewable sources is already possible.

The intermittency of other sources such as wind and solar photovoltaic can be addressed by interconnecting power plants which are widely geographically distributed, and by coupling them with peak-load plants which can quickly be switched on to fill in gaps of low wind or solar production. Numerous regional and global case studies – some incorporating modeling to demonstrate their feasibility – have provided plausible plans to meet 100% of energy demand with renewable sources.

Speaking at a solidarity vigil held in Manila, the day after the Fukushima nuclear disaster, in 2011. Photo: Jenny Tuazon

Nuclear: Not on my watch

I remember attending a Committee on Appropriations hearing at the House of Representatives in 2009, where the chief proponent for the BNPP, then-congressman Mark Cojuangco made a comment that only 60 people died in the Chernobyl catastrophe. That comment caught the ire of a nun in the audience who questioned the value that Cojuangco puts on life.

“Only 60 people died! That’s 60 people who could have been someone’s parent, child, sibling, spouse or friend!” she said in shock.

Ultimately, nuclear power is not just about technology or economics, but about the value we put on life and what kind of future we want for ourselves and for our children.

There really is no point in trying to revive the BNPP. It will only cost the Filipino people more – not just in terms of rehabilitation and operations, but also in terms of health, environment impacts, disaster preparedness, and sustainable development. Japan and European countries, which have had long histories with nuclear power, are now moving away from nuclear. We should already have learnt our lessons from Fukushima, from Chernobyl, and from the historical burden that we have experienced with the BNPP even though it was never operational, its about time that we move on and go renewable.