By Rowland Davis and James Buchen

August 29, 2020

Photo by Crusenho Agus Hennihuno

The tension is spelled out in the title. Can “Big Oil” and “green shoots” possibly be used in the same breath? European oil companies are making the case that they can.

In our previous blog post, we described the current state of the oil industry and how transitioning to a carbon-free economy will dramatically decrease demand for oil. The question is: just how quickly will global oil demand drop and how will the oil industry will react to that drop? Here are three possibilities:

- The oil industry may ignore reality and conduct business as usual for as long as possible. The risk there is that demand will drop so quickly that oil businesses will have no viable endgame – other than bankruptcy. The U.S. coal industry already seems to be facing this scenario.

- The oil industry may plan for an orderly downsizing of their business, with transparency to shareholders and other stakeholders. This would entail stoppage of most growth-related activities and investments, with cash directed back to shareholders instead.

- The oil industry may plan to shift their business into new areas that provide sustainable growth opportunities.

The U.S.-based oil super majors (ExxonMobil, Chevron and ConocoPhillips) seem, for now, to be stuck in a mostly business-as-usual mode. European oil companies, however, are talking about real shifts in their business plans that would align more closely with the growing transition to a carbon-free economy. So is all the talk just more greenwashing that we have seen from them before (for example, the BP ad campaign “Beyond Petroleum”)? Or could this really be the start of some green shoots in the oil business? Time will tell, but the European “Big Oil” majors have been making announcements about shifting to a greener business model.

First, let us consider a company that has already made the shift from oil to renewables: the Danish company Ørsted. Ørsted started oil drilling and oil production in the North Sea in the early 1970’s. While not an “super major”, the company was a significant player in the oil world for many years. In the early 2000’s, Ørsted began to pioneer off-shore wind farms and then continued to expand that part of their business. Finally, in 2017, Ørsted sold its last remaining oil and gas assets, completing its transition into a renewable energy business, after building on the technological synergies between off-shore oil drilling and off-shore wind farming. It now operates the world’s two largest off-shore wind farms, with even larger ones planned. Since their 2017 announcement, Ørsted’s stock appreciated by 155% over the following three years while the S&P Oil & Gas EP Index dropped -60%.

Then there is BP, which has made the most ambitious and specific plans of any oil major to date. The company installed a new CEO, Bernard Looney, last February, and he quickly announced his intention to make the company “net-zero” by 2050 but said details would come later in the year after strategy plans were developed. His lack of details prompted some skepticism, but in early August, BP did provide a more detailed plan which 350.org co-founder Bill McKibben called “…the most serious announcement from an oil major….Far from perfect, but far from normal.” This plan was announced shortly after BP took a major write-down on oil and gas reserves, and on the day BP announced one of company’s worst quarterly profit losses as well as a cut in the company’s dividend rate. But that same day, its stock price actually went up. BP’s forward-looking plan includes these goals for 2030:

-

- A 10-fold increase in low-carbon energy investment (including renewables, carbon capture, and hydrogen), to the tune of about $5 billion a year, although the bulk of spending ($14-$16 billion per year) will still be on fossil fuels.

- Renewable power capacity will rise 20-fold.

- Oil and gas production will fall by 40%, from 2.6 million barrels of oil equivalent per day (boe/d) in 2019 to 1.5 million boe/d, with a focus on profitable regions that are less carbon intensive.

- Emissions from operations will drop by one-third, and the carbon intensity of BP’s products will fall by 15%.

The two most notable features of the plan are (1) that these goals are set for 2030, not 2050, and (2) the explicit acknowledgement of an expected 40% cut in production over the next ten years. The 2030 date means that BP’s actions can be monitored more immediately, and the speed of the production cuts is something other companies will have to consider, as Bill McKibben and Tom Steyer mention in the GTM article “2030 is the New 2050: The Oil Industry Begins to Unwind.” Climate experts applaud these plans by BP but also say that more needs to be done.

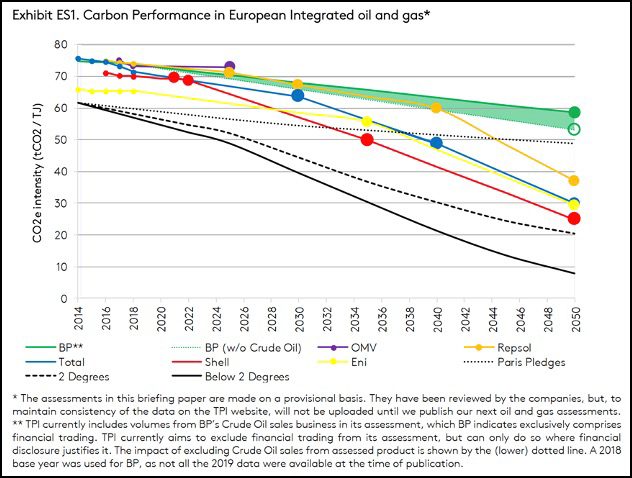

Among the other European oil majors, level of commitment to change is more general and less ambitious. The Spanish company Repsol was the first to commit to a net-zero-by-2050 strategy last December, and in short order, all other European oil companies followed suit. The specific nature of the commitments vary from company to company, and so far none have been as specific as BP about how changes will be accomplished. In May, the Transition Pathway Initiative analyzed the various commitments of the European oil companies and compared them to targets outlined in the 2015 Paris Agreement. (Note: this analysis was done before BP’s recently announced detailed plan regarding its 2030 commitments.):

Source: Transition Pathway Initiative

The chart above makes it clear that more needs to be done: even stronger commitments, specific action steps, shorter-term targets, more transparency, and an end to further investment in oil exploration. But it is an encouraging step in the right direction.