At the end of February the scenes in the South Pacific atoll island nation of Kiribati were dramatic and frightening. Waves crashed across the lagoon side of South Tarawa, the capital of Kiribati, swamping everything in their path. For the locals, there was no where to go as the waves left a trail of destruction, flooding the hospital in Betio, destroying food crops and fouling the already severely limited freshwater lens.

Michael Foon, from the National Disaster Management Office described the impact:

Where the hospital is completely flooded and the surrounding area, resulted in power cuts. This is the first time that we’ve seen this sort of extensive flooding, it goes maybe 200 metres in-shore, and it’s impacting people because they depend on water wells that are now salty. You start seeing breadfruit trees with brown leaves, dropping their leaves and fruit.

The destruction was widespread, with the crucial causeway connecting two parts of South Tarawa closed to one lane as it began to disintegrate in some sections.

The swamped hospital in Betio. Photo credit: Kiribati Abau Ni Koaua

It’s hardly surprising that there is a palpable sense of anxiety and fear about the future of the islands. That’s compounded by the media-fuelled speculation and sensationalism about the entire population of Kiribati becoming climate change refugees, which has driven and also feeds off this fear. Yet the situation facing Kiribati is complex, and that complexity is usually not well understood or reported on. Understanding this complexity is critical to talking about the future of Kiribati — as outsiders — with the care, respect and dignity the people deserve. To understand what is happening in Kiribati now, we need to understand the historical climatic and oceanic trends, and a bit of local history. There are three key factors driving this havoc upon South Tarawa.

1. The tricks of El Niño & La Niña

From the 1970s until about 2000, there was rapid, unplanned development in South Tarawa, as thousands of people moved in from the outer atolls to South Tarawa. During this period, there was also a dominance of the El Niño weather pattern. In El Niño years water levels tend to be pushed downward, while in a La Niña year, sea levels tend to be pushed upward. So South Tarawa saw rapid development in a context where sea levels were on average lower than if it had been a period dominated by La Niña years. That meant that development and settlement became increasingly bold, as sea walls were built, and homes built on increasingly marginal land.

In 2000, a sort of natural switch flicked (this is what is called the Pacific Decadal Oscillation), and we have since seen a predominance of La Niña years, and with that, sea levels forcing upward.

2. King tides

The effect of the upward pressure of La Niña on sea levels, is that over the last decade or so we have seen more frequent and higher high tide levels (often called king tides) — not just in Kiribati but in other atoll islands, including Tuvalu and the Marshall Islands. Tides are a natural phenomenon caused by the alignment of the sun, moon and Earth.

3. Climate change is causing sea level rise

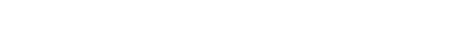

At the same time, underlying sea level rise caused by climate change, continues to push tide level higher. That contribution caused by climate change while relatively low at present, is as the graph below shows, on track to becoming significantly more devastating. It’s this concoction of forces that is wreaking serious havoc in South Tarawa and across many atoll islands But whether life on the atolls become untenable depends depends on our course of action now.

Source: “Climate Variability, Extremes and Change in the Western Tropical Pacific” (2014)

What does the future hold for Kiribati?

Scientific modelling, and history suggest that the current trend of La Niña domination is likely to continue for another 10-20 years. That means continued upward pushing of sea levels. Following that, it is likely that it would flip back into El Niño dominance for another 20 – 30 years, which would work to suppress sea levels somewhat, perhaps giving something of a reprieve from climate change forced sea level rise.

But just how much reprieve might be offered depends hugely on how the rest of the world acts now to curtail greenhouse gas emissions. To give Kiribati any hope of reprieve, we know that at least 80% of known fossil fuel reserves must stay in the ground. Thanks to recent research at University College London, we now also know the geographical distribution of where fossil fuels must stay in the ground. The work that the global community needs to do now is to put an effective freeze on fossil fuel extraction. That’s work that needs a grassroots movement to achieve, and fortunately, we are seeing that rise all over the world – from the Pacific Climate Warriors, to theUkrainian Youth Climate Association.

But back to the immediate future for Kiribati. While there has been a lot of talk about the future of Kiribati, little has been done on the ground to increase the resilience of infrastructure and the community to these events in the immediate future. There is little public infrastructure that is not at risk from coastal hazards on Kiribati, which has a population density comparable to Hong Kong or New York.

It’s clear that there is incredible urgency to supply just basic needs and sanitation for residents in South Tarawa. Meanwhile, urgent aid and support is required to rebuild more effective seawalls, rebuild the hospital and other infrastructure on raised platforms, and to relocate parts of the population who are living on the most marginal land to more stable land. There are basic, urgent issues to deal with, and the Kiribati Government needs to get cracking. The global community also needs to play a role in delivering critical and urgent aid so that the solutions are not just a patch up job, but a well thought out plan that will keep Kiribati a liveable nation.

The work of adapting to increasing sea levels also needs to be led from the ground up. In amongst the desperation of the situation, there are good organisations, like The Island Rescue Project that are working to provide emergency supplies for the hospital, and sharing stories of what is happening in Kiribati.

Through 350.org Pacific, we work with a network of i-Kiribati that have been educating their communities about climate change, and pushing for global action to reduce emissions. It’s clear now that that work now has to move into a new phase of organising to keep life liveable in Kiribati. That’s why next week, one of our team, Fenton Lutunatabua will be there as the king tides once more reach their peak, to gather and share stories from locals on the ground and to support our Kiribati team to identify a path ahead in this time of crisis.

It’s critical that the complex factors that are driving the current crisis in Kiribati are understood – because this crisis is not just driven by climate change, but by land use choices, and by natural variation. Understanding that can empower a response that is perhaps more hopeful than what the media and many others tell us about Kiribati. At the same time, the urgency for action to keep fossil fuels in the ground is as pressing as ever. Our thoughts are with all in Kiribati, stay strong.

My thanks to Doug Ramsay from the National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research in New Zealand for his help in providing the scientific background and basis to the situation in Kiribati.